Defence and National Rehabilitation Centre (DNRC)

and replacement for Headley Court at Stanford Hall

Between 1985 to 2018, Headley Court, Surrey, served as the British rehabilitation centre for wounded military personnel. Towards the end of this period, however, the centre needed to be refurbished and enlarged to cater for new state of the art treatment. In light of this, Gerald Grosvenor, the 6th Duke of Westminster, saw an opportunity: to further improve the military’s rehabilitation expertise and share it with the NHS for the benefit of the nation as a whole. Thus the Defence and National Rehabilitation Centre was born.

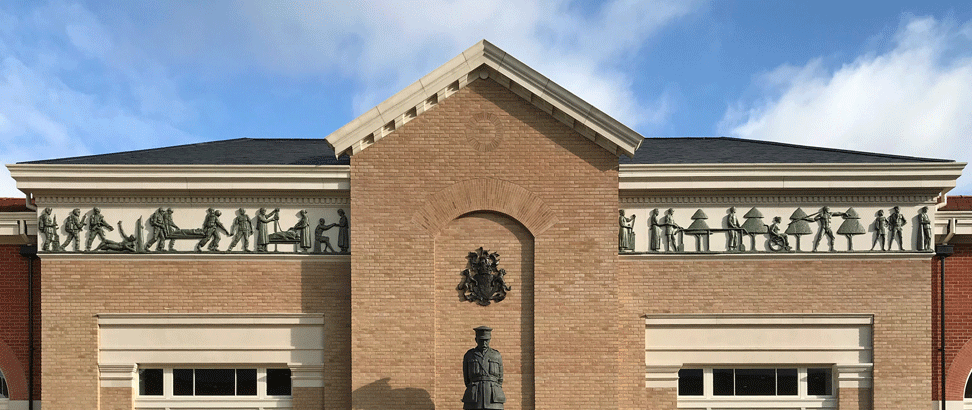

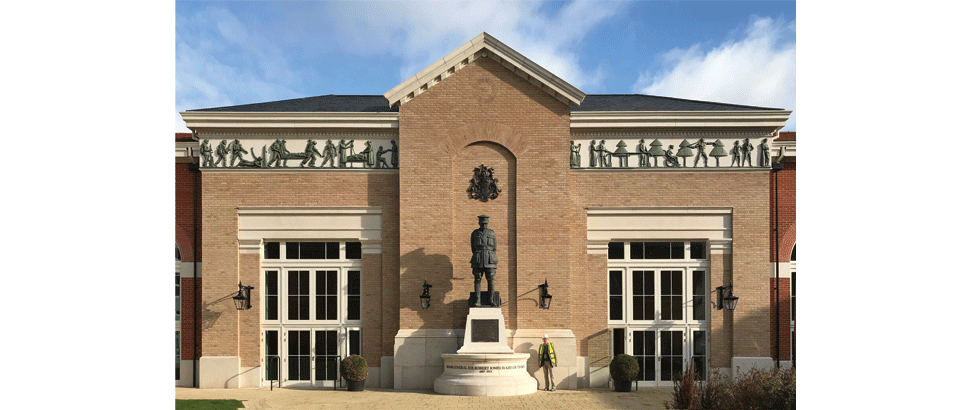

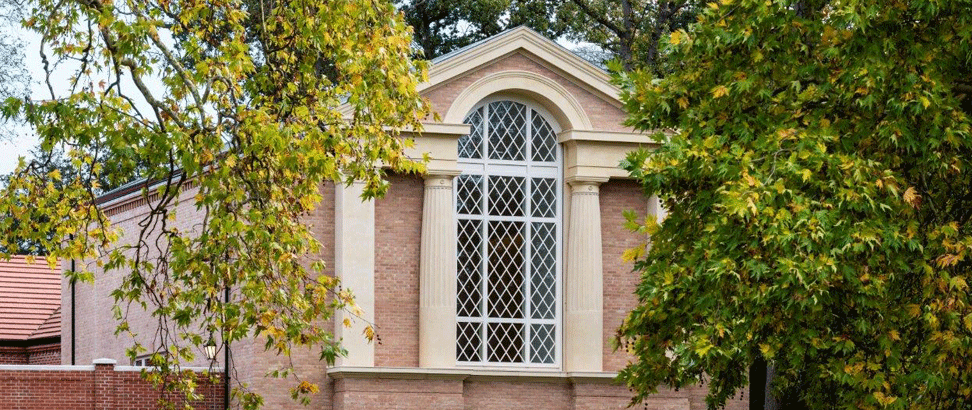

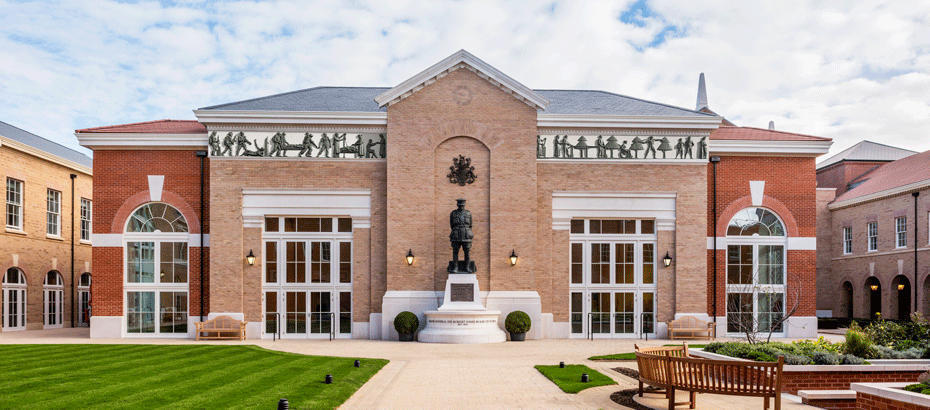

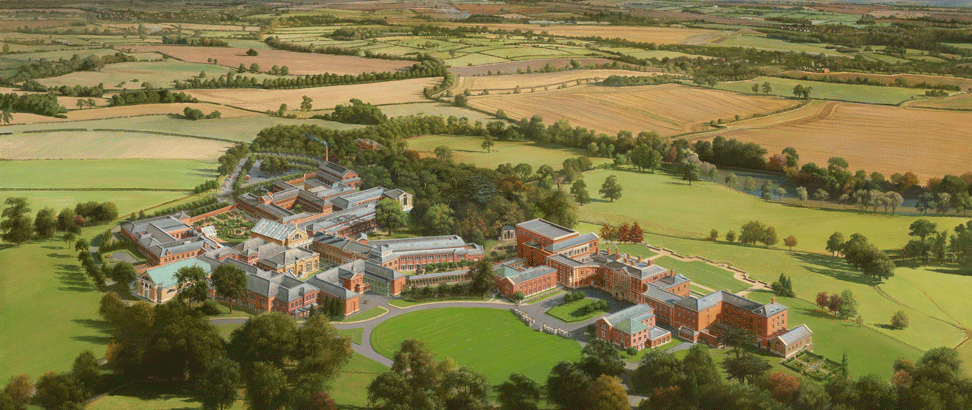

In response to increasing neurological evidence of the benefits of traditional architecture to wellbeing, namely in its use of the human scale and symmetry, Stanford Hall, a grade II* listed country house in the heart of the Leicestershire was chosen for the project, and John Simpson Architects, for whom the significance of architecture to the public realm is a core belief, for its design and expansion. The guiding principle of the 400,000 square foot facility - four times the size of its predecessor, the largest collection of new classical buildings in the UK since Lutyens - was to develop in line with the character of the architecture and park, so that the project’s scale never surpassed that of the Hall, which was to be restored in the process. Spatially, this posed a significant challenge. The answer lay in a series of buildings, grouped together to enclose gardens, courtyards and cloisters that flow seamlessly from one into the other with views onto the outlying parkland, punctuated by pavilions housing facilities such as gyms and hydrotherapy pools. Not only does this create a human-scale sanctuary away from the pressures of the outside world, where every patient can find a tranquil spot, but a logical flow of people including inpatients, outpatients, visitors, staff and health professionals, with space for further development. Beyond this, the design also allowed for the renovation of an existing 290-seat - including 30 wheelchairs - Art Deco theatre to act as a cinema, recital room, performance and conference space, as well as the old sprung-floor Badminton Court, complete with a new acoustic ceiling and bespoke audio-visual system. As much as the new centre relies on medicine, therefore, so too does it rely on the healing powers of architecture: a language of architecture that is known to speak to people, encouraging them to speak themselves.

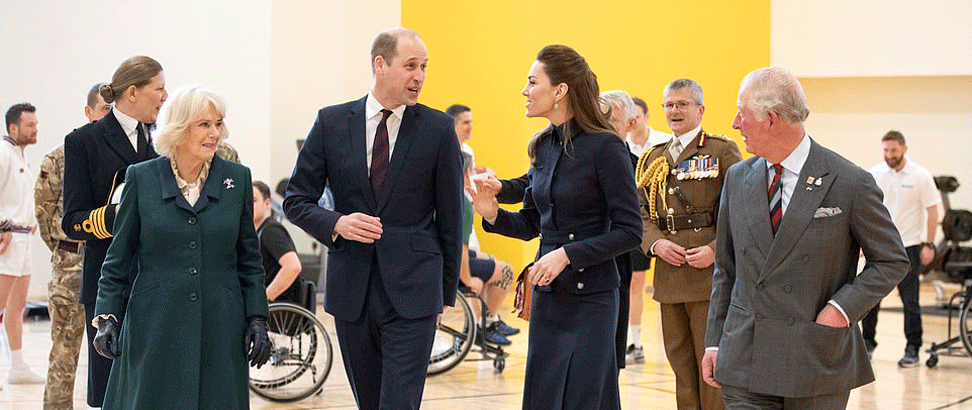

The Defence and National Rehabilitation Centre was accepted as a gift to the nation by the Prime Minister in 2018 in the presence of HRH The Prince of Wales when he was The Duke of Cambridge, and Hugh Grosvenor, the 7th Duke of Westminster.